Three-dimensional Geometric Ornamentations: Muqarnas

As many people know, Islam forbids idolatry, the worship of images of particular people or objects. For this reason, figurative art that depicts specific people or objects, especially in religious contexts, is viewed unfavorably. So, the ornamentations in architecture strongly associated with religion, such as mosques and madrasas, tend to feature geometric patterns and plant-like motifs rather than depict figures.

When thinking about the use of geometric ornamentations in Islamic architecture, the first examples that come to mind are often flat and two-dimensional, such as decorative wall and floor tiles, mosaics, and wooden carved door. At the Qalawun charitable endowment complex as well, we see marble mosaics on the floor, and even windows used as the motif for the logo mark of this project, all based on geometric principles.

But,ornamentations in Islamic architecture not only two-dimensional. Muqarnas, the subject of this article, is a typical example of three-dimensional geometric ornamentation distinct to Islamic architecture.

Muqarnas are widely seen throughout the Islamic world (as far west as Spain and as far east as Central Asia). These architectural ornamentations are typically concave shapes comprising curved surfaces. Although they may give the appearance of being a complex arrangement of organic curved surfaces, they are actually designed according to particular geometric rules. Commonly found on the underside of domes and in sections where the width of a minaret narrows, they create a smooth upward-sloping gradient, seamlessly connecting sections that would otherwise come together at right angles.

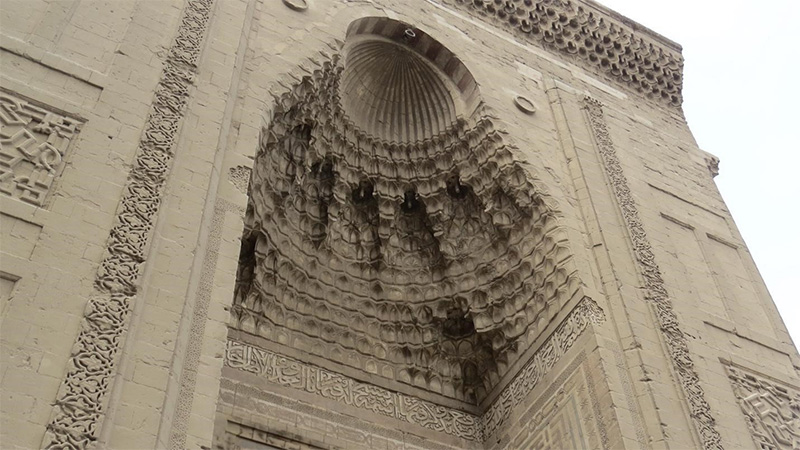

Some outstanding and well-known examples of muqarnas include the hall of Abencerrajes in Alhambra (Granada, Spain) and the iwans of the Shah Mosque (Isfahan, Iran). This style of ornamentation was also popular in Egypt during the Mamluk Sultanate when the Qalawun complex was built. About 70 years afterward, a large ornate half-dome muqarnas was fashioned at the entrance to the complex of Sultan Hasan.

(Cairo, built in 1356) (photo by author)

©Qalawun VR Project

The muqarnas at the Qalawun complex are not as conspicuous, but they do exist. They decorate the periphery of the minaret, and small muqarnas-like surfaces are used to accent the curvature of the ceiling in the mausoleum’s vestibule. (These can be seen in the VR tour.)

©Qalawun VR Project

Theories about the origin of muqarnas suggest they may have roots in the decorations of pre-Islamic handicrafts, or may have emerged from the techniques used to build arches. Early examples of fully-realized muqarnas used in buildings include some from around the 10th century that are believed to have been strictly functional elements, supporting the structures above.1 Over the years, the shapes became more complex. Eventually, just the curved surfaces of muqarnas were used as design elements, giving them a more decorative nature. This transition from functional structures and materials to purely decorative ones was not limited to the Islamic world. It is commonly seen in architectural ornamentations. 2

1 Fukami, 1998: 270.

2 For example, parts called “kumimono” found in Buddhist architecture were originally structural components protruding from pillars to support horizontal components. But in Zen temples, they came to be arranged in large numbers in areas unrelated to the structure, for decorative purposes (called “tsumegumi”).

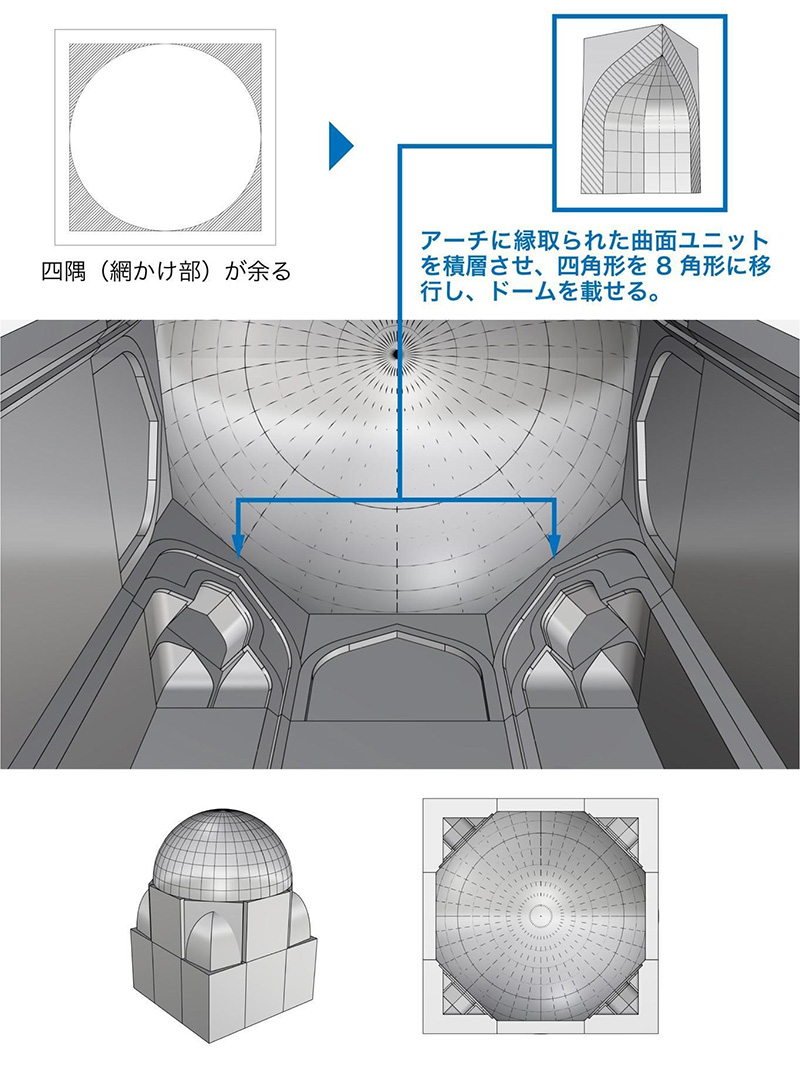

Early functional muqarnas (and muqarnas-like building components) consists of units designed to fill the space between two half-arches that intersect at right angles when viewed from above. A number of such units are stacked like steps to form a muqarnas. They protrude inward from four corners of a room to support the components on top of it. In architectural terminology, such components to support other ones are commonly known as “corbels”. A corbel is a structural component that extends horizontally from a wall or column, and upon which rests a beam or roof.

They support the cross-beam above.

(Illustration by the author)

©Qalawun VR Project

The dome is an important component in Islamic architectural culture. Dome structures are commonly supported by muqarnas. If you live in a place where you don’t often see architectural domes, it might not occur to you that the circular base of this hemispherical shape can leave the four corners of the square-shaped room below it. exposed. Europe, the Islamic world, and other regions where domes are more common have devised a variety of ways to address this issue. Originally, the role of muqarnas was to bear the load of the dome above, and also to smoothly transition the design of the space from square below up to circular above. From its functional origins, muqarnas thereafter evolved into mainly ornamental element for domes.

(illustrations by the author)

©Gentaro Yamada

Muqarnas were originally small items used on the domes of small-scale mausoleum buildings, but the number of curved surfaces increased as the domes grew in size. As dome construction techniques improved3, muqarnas functioned less as support for domes, and grew more decorative with complex shapes that adorned the underside of domes. Many of the larger-scale examples in Egypt, including those of the complex of Sultan Hasan shown above, are stonework. Also, because the muqarnas were integrated into the structure of the building, they are believed to have been created with some awareness of their supportive strength.

3 In regions where buildings are constructed by stacking components like blocks, dome construction techniques was important in providing roofs to cover large spaces.

Meanwhile, another type of muqarnas examples can be seen in other regions such as Iran. Those examples are made by finishing the surfaces of the frame assembled underside the pre-made smooth dome with plaster and tiles

In these examples, the structure of the muqarnas and the structure of the dome are completely separate.4 Thus, although referred to with the same term, “muqarnas”, we see that their construction method varied considerably by region and period.

4 O’Kane, 1987: 88–91.

In future articles, I will provide a more detailed history of muqarnas, and discuss the geometric principles used to create them.

References

Naoko Fukami, Studies on Muqarnas-vaulting in the Islamic Architecture, Ph.D. thesis, Yokohama National University, 1998(in Japanese).

Bernard O’Kane, Timurid Architecture in Khurasan, Costa Mesa: Mazdâ Publishers in association with Undena Publications, 1987.

About copyright

Click here for copyright information regarding the illustrations and photographs used above.

English translation: Jeff Gedert